Member of Russell Bedford International, a global network of independent professional service firms.

Your tax return is filed and you’ve even received your refund check. Naturally, you had hoped to be done with taxes for another year. But what do you do if you discover a mistake on your return? Should you file an amended return? Depending on a few circumstances, filing a 1040X may not end up working in your favor. Before you decide to amend your tax return, here are some things to consider.

If a correction will result in a substantial additional refund, usually your best option is to file the amended return. However, there some caveats:

If you discover errors on your tax return that will result in an additional tax obligation, you are required to correct the errors and file an amended tax return, along with the amount due.

If the IRS discovers your tax error before you do, they could add interest and penalty fees. The sooner you file the amended return and pay the tax that is the due, the better.

Finding an error on your tax return can be unsettling, but rest assured there are ways to fix the problem. Contact Cray Kaiser today to determine the best solution for you.

State taxes used to be simple. You have a store in Chicago; you pay Illinois tax. You have a warehouse in Indianapolis; you pay Indiana tax. But what if you have sales people visiting Denver? Or you work with an online reseller with a location in Denver? Do you need to pay Colorado tax? The tax term used when determining in which localities a business must pay tax is called nexus. How nexus works often stumps even the most tax-savvy business owners, especially with the impact of online sales and constantly changing rules. By understanding and correctly determining nexus, you can avoid unnecessary penalties and stop asking yourself, “do I have nexus?”

Simply put, nexus is the factor that dictates a states’ ability to assess tax. Nexus, or sufficient presence, is determined by a number of factors, including a business’ temporary or permanent presence of people or property in a state.

Some aspects of nexus are clear. For example, if a business has a permanent location in a particular state, there is no federal limitation on a states’ ability to subject the business to income tax. Beyond the obvious, however, each state defines nexus in its own way, and differently for different tax types.

For example, states may consider the following when determining nexus:

States’ definitions of nexus are adapting to evolution in technology. Constantly changing technology changes the way we do business. As online sales grow, businesses conduct more and more business out of state. In addition, advances in technology make it easier for states to collect information about sales occurring within their state.

Additionally, given budget constraints, states are becoming more aggressive in seeking out additional tax revenue.

The lack of a consistent definition of nexus state-to-state creates confusion and exposure to tax liability. Small businesses with little to no internal accounting departments may not have the time or the expertise to properly assess nexus. For businesses with interstate activity that only file a home state tax return, the potential tax exposure and tax complexity can be a significant cause for concern.

A federal nexus definition has been spoken of for years, but thus far has not become a reality. In the meantime, it’s important for business owners to understand their risk. Consult with an accountant to determine how nexus is defined in the states in which you do business. Find out if you need to register to do business in other states or file additional state tax forms. Explore voluntary disclosure programs and statutes of limitations. Most importantly, any time you have a question about whether or not you have nexus in a particular state, check in with your accountant.

Don’t be stumped by your nexus questions. Contact Cray Kaiser today.

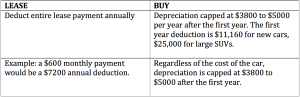

John’s skills and talent have resulted in a great deal of success for the company. His sales job involves quite a bit of driving throughout the Midwest. You’ve decided you want to reward his efforts and success with a company car. Before you tell John, you have a decision to make. Will his car be leased? Or will the company buy it outright? What kind of impact does leasing versus owning have on the company’s tax situation? Several factors impact this decision, including how long the car will be kept and how consistently the car will be driven.

How long will the company keep the car?

If the company plans for John to keep the car longer than a leasing period, it likely makes sense to buy the car outright. If the company plans to reward John with new cars fairly frequently, a lease may make more sense. Weigh the annual lease payments against the annual deductions.

Will the use of the car be consistent year-to-year?

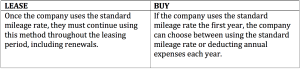

Regardless of whether you lease or buy John’s car, the company has a choice to make. They can either deduct all expenses, including gas, service, repairs, depreciation/lease expenses and insurance, or use the standard mileage rate (54¢ per mile in 2016). Tolls and parking can be expensed in addition to the standard mileage rate.

Only mileage associated with business use can be deducted, and a log must be kept to separate business mileage from personal use. In order for the expenses/mileage to be fully deductible to the company, the employee using the car must have the personal portion of the auto use recorded on their W2 as a fringe benefit. The pretax benefit to the employee far outweighs the small amount of additional income associated with the fringe benefit.

Different rules apply to switching between deduction methods for leasing versus buying.

If John’s use of the company car will vary from year to year, buying the car will offer more flexibility. In addition, inconsistent use can also create costly leasing expenses. Leases include an annual mileage allowance with per mile surcharges for overages.

Choosing the best option between leasing and buying John’s new car means considering tax implications and predicting the use of the car. Careful planning including consideration of when John’s car will be replaced and how consistent his travel will be will help you reach the best decision for your company.

If you are facing a similar decision and want to talk through the tax implications, we would be happy to help. Contact us today.

2016 W2 Forms must be filed with the Social Security Administration (SSA) by January 31, a month earlier than in past years. The deadline to mail W2s to employees remains January 31. The date was accelerated as an attempt to reduce fraud.

Follow these tips to avoid errors:

Meeting the new deadline can be stress-free if you take the time to prepare in advance. Throughout the next year, create a set process for collecting taxable benefit data. For example, require any employees who use a company car to maintain and submit an auto log and collect the log on a monthly or annual basis.

We are happy to help calculate the value of your employees’ taxable benefits for your W2s. For help or to learn more about W2 preparation and filing, contact us today.

Your toga-partying, test-cramming days were years ago. So why should you care about tax credits for education? Because if you’re doling out some dollars for keeping up your skills (or your employees’), there are likely tax benefits to you or your company.

How Employers Benefit

Encouraging your employees to boost their skills with continued education impacts your bottom line in more ways than one. Employees who receive assistance covering educational costs are more motivated and loyal. They do not have to pick up the costs as income. They apply their new skills to help you improve your business. And the costs are tax deductible to boot. It’s a win-win.

It’s simple:

How Individuals Benefit

If your employer does not provide an educational expense reimbursement plan, you can still receive a tax benefit in the form of the Lifetime Learning Credit. Whether you are pursuing a degree in your field or simply taking a class to help you improve your skills, you can take a credit for up to 20% of up to $10,000 in tuition costs and related expenses, for a maximum credit of $2,000.

Limitations depend on income level. In 2023, for example, a married couple’s credit limitation starts at an adjusted gross income level of $160,000, and the benefit phases out completely at adjusted gross income of $180,000 or higher. As the rules for a single taxpayer are different, and the phaseout amounts are adjusted annually, call Cray Kaiser to see which limitations apply to you.

How the Self-Employed Benefit

When you’re self-employed and dealing with a tax rate as high as 37%, investing in your education can benefit your bottom-line not only by improving your skills but also with some welcome tax deductions. As a self-employed taxpayer, business-related educational costs can be deducted directly against your business income. How does that impact your tax situation? Let’s look at an example of an attorney who is in the highest tax bracket. An attorney pays $1,000 for a seminar put on by a local law firm accredited for law coursework. By deducting the $1,000 in course fees, he saves at least $370 in federal taxes. That’s a tax deduction with some impact!

While a Rodney Dangerfield-style deep dive back into your college days may not be in your future, hopefully you or your employees will take some classes along the way. You’re no doubt aware of the many benefits of updating and improving your skills and those of your team members. Be sure to consult with your accountant to understand how to take advantage of the tax benefits of continued education as well.

Hearing marketing advice from your accountant may be surprising and unexpected, but if you are working on your IRS Tax Form 990—the return filed by non-profit organizations—it’s exactly what you should hear. At Cray Kaiser, we refer to Tax Form 990 as your “resume for big donors.”

Yes, your accountant checks over every detail to be sure that the IRS—the number one audience for Form 990—continues to consider the organization tax-exempt. But did you know that Form 990 is also available to and frequently read by the general public?

Imagine a potential donor who is planning to make a large donation and is choosing among three organizations, one of which is yours. The donor pulls up the three 990 forms to learn more. She reviews mission statements, achievements and financials. She considers how much money went to the mission versus how much was spent on advertising and overhead. She examines Board of Trustees and senior management lists, possibly researching more about those involved with the organization.

How does your Form 990 compare? Will she choose your organization over one with a Form 990 that effectively communicates the mission of the organization and persuades readers to support the cause?

It’s not often that your tax form serves as a marketing tool, but in this case, that’s exactly what it is. Use this opportunity to persuade that donor with money to bestow that your cause it the most deserving one. And while you may not turn to your accountant for advice on your new logo or advertising campaign, the advice to use your Form 990 as a marketing tool can make the difference between getting that big donation or having it pass you by.

If you have questions about Tax Form 990, please contact Cray Kaiser today. We’re here to help!

If you fill out your own 1099, it always seems less daunting than other tax forms due to its shorter length. But did you know one little mistake can cost you $100 per infraction? Don’t let this “little form” bite you with expensive penalties later on. All mistakes are easily avoidable if you’re thorough.

Although the tax code contains some exceptions, income is generally taxable in the tax year received and expenses are claimed as deductions in the year paid. But “carryforwards” and “carrybacks” have special rules. In this case, certain losses and deductions can be carried forward to offset income in future years or carried back to offset income in prior years, providing tax benefits.

Here are four examples:

Capital losses. After you net annual capital gains and capital losses, you can use any excess loss to offset up to $3,000 of ordinary income. Remaining losses can be carried over to offset gains in future years. The carryforward continues until the excess loss is exhausted. For example, suppose you have a net capital loss of $10,000 for 2023. After using $3,000 to offset ordinary income on your 2023 return, you carry the remaining $7,000 to 2024. The excess loss is first applied to your 2024 capital gains, and then to as much as $3,000 of your ordinary income. Any remaining loss is carried forward to 2025 and future years.

Charitable deductions. Your annual charitable deductions are limited by a “ceiling” or maximum amount, as measured by a percentage. For example, the general rule is that your itemized deduction for most charitable donations for a year can’t exceed 50% of your adjusted gross income (AGI) (60% for years through 2025). Gifts of appreciated property are limited to 30% of your AGI (20% in some cases) in the tax year in which the donations are made. When you contribute more than these limits in a year, you can deduct the excess on future tax returns. The carryover period for charitable deductions is five years.

Home office deduction. If you qualify for a home office deduction and you calculate your deduction using the regular method, your benefit for the current year can’t exceed the gross income from your business minus business expenses (other than home office expenses). Any excess is carried forward to the next year. Caution: No carryforward is available when you choose the “simplified” method to compute your home office deduction.

Net operating losses (NOLs). Historically, NOLs could be carried back two years and forward 20 years. Under current law, NOL’s can only be carried forward in most cases. Give us a call for help in maximizing the tax benefits of carryforwards or carrybacks.

Please note that this blog is based on tax laws effective in December 2023, and may not contain later amendments. Please contact Cray Kaiser for most recent information.

Changes to the federal income tax code can prompt you to review the legal structure of your business. The 2018 TCJA lowered the corporate tax rate to 21% while barely adjusting the highest individual rate to 37%. At the most basic level, businesses are taxed as either stand-alone or pass-through entities, and a significant difference between corporate and individual tax rates is reason for a new assessment.

If you’re debating between operating as a C corporation or an S corporation, here are three tax aspects to consider.

1.) Income taxes. A difference you’re probably aware of between the two types of corporations is the way earnings are taxed. C corporations are stand-alone entities and pay federal income tax at the corporate level, based on business earnings. If the corporation has a loss, the loss offsets business income in past or future years.

S corporation earnings and losses are passed through to you, as a shareholder. Earnings are taxed on your individual income tax return at your personal tax rate. This is true even if you receive no cash from the business. Losses can offset other types of income such as wages, portfolio, or retirement income.

2.) Ownership. Tax rules limit the number and type of shareholders who can own an interest in your S corporation. For example, an S corporation can have no more than 100 shareholders, and they must all be U.S. citizens or residents. In addition, your S corporation can issue only one class of stock, meaning all shareholders have the same liquidation and distribution rights. When you form a C corporation, foreign owners can hold stock in your business. You can also issue stock with different ownership privileges, such as preferred stock, which grants priority in receiving corporate dividends.

3.) Dividends and distributions. In general, when corporate income is distributed to you as a shareholder, the distribution is a dividend. Whether your corporation is formed as a C corporation or an S corporation, the business gets no deduction.

However, as a C corporation shareholder, you’re required to include income distributions on your personal tax return. In effect, distributions are taxed twice, once on the corporate return and once on your return.

When you own stock in an S corporation, distributions can be considered a return of the money you invested in the business (and has already been taxed at your personal level). The distinction means you may not owe income tax, assuming you have basis in the corporation.

Many tax and nontax reasons will affect your choice of the best type of structure for your business. Please call our office for a complete evaluation.

Mutual funds offer an efficient means of combining investment diversification with professional management. Their income tax effects can be complex, however, and poorly timed purchases or sales can create unpleasant year-end surprises.

Mutual fund investors (excluding qualifying retirement plans) are taxed based on activities within each fund. If a fund investment generates taxable income or the fund sells one of its investments, the income or gain must be passed through to the shareholders. The taxable event occurs on the date the proceeds are distributed to the shareholders, who then owe tax on their individual allocations.

If you buy mutual fund shares toward the end of the year, your cost may include the value of undistributed earnings that have previously accrued within the fund. If the fund then distributes those earnings at year-end, you’ll pay tax on your share even though you paid for the built-up earnings when you bought the shares and thus realized no profit. Additionally, if the fund sold investments during the year at a profit, you’ll be taxed on your share of its year-end distribution of the gain, even if you didn’t own the fund at the time the investments were sold.

Therefore, if you’re considering buying a mutual fund late in the year, ask if it’s going to make a large year-end distribution, and if so, buy after the distribution is completed. Conversely, if you’re selling appreciated shares that you’ve held for over a year, do so before a scheduled distribution, to ensure that your entire profit will be treated as long-term capital gain.

Most mutual fund earnings are taxable (unless earned within a retirement account) even if you automatically reinvest them. Funds must report their annual distributions on Forms 1099, which also indicate the nature of the distributions (interest, capital gains, etc.) so you can determine the proper tax treatment.

Outside the funds, shareholders generate capital gains or losses whenever they sell their shares. The gains or losses are computed by subtracting selling expenses and the “basis” of the shares (generally purchase costs) from the selling price. Determining the basis requires keeping records of each purchase of fund shares, including purchases made by reinvestments of fund earnings. Although mutual funds are now required to track and report shareholders’ cost basis, that requirement only applies to funds acquired after 2011.

When mutual funds are held within IRAs, 401(k) plans, and other qualified retirement plans, their earnings are tax-deferred. However, distributions from such plans are taxed as ordinary income, regardless of how the original earnings would have been taxed if the mutual funds had been held outside the plan. (Roth IRAs are an exception to this treatment.)

If you’re considering buying or selling mutual funds and would like to learn more about them, give us a call.

*This newsletter is issued quarterly to provide you with an informative summary of current business, financial, and tax planning news and opportunities. Do not apply this general information to your specific situation without additional details and/or professional assistance.