Member of Russell Bedford International, a global network of independent professional service firms.

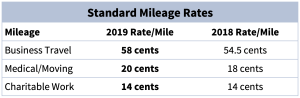

The updated mileage rates for travel for 2019 have been confirmed by the IRS. The standard business mileage rate is increasing by 3.5 cents to 58 cents per mile. The medical and moving mileage rates are also increasing by 2 cents to 20 cents per mile. Charitable mileage rates remain unchanged at 14 cents per mile. Please see the chart below for quick reference:

It is important to properly document your mileage in order to receive full credit for your miles driven. As always, should you have any questions or concerns please contact Cray Kaiser at 630-953-4900.

“Wayfair” is the new buzzword in sales tax reporting, and for good reason. You have likely heard that the Supreme Court’s decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. has resulted in businesses being required to collect and remit sales tax to certain states in which they have no physical presence. Have you wondered how this change affects your requirements for income tax filing?

While the Wayfair decision did not directly impact income tax nexus, the removal of a physical presence requirement for sales tax nexus may encourage more states to enact a sales factor indicator for income tax nexus. In fact, states such as Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Michigan, New York, and Tennessee already have bright-line tests in place, which consider a business with certain levels of property, payroll or sales in the state to have income tax nexus. Other states, such as Ohio and Washington have enacted gross receipts taxes, which come into play once a business reaches a certain level of activity in the state.

It’s important to note that the Wayfair decision does not overrule P.L. 86-272, which allows businesses to send representatives into a state to solicit orders for personal property without being subject to a tax based on net income. However, a state may still impose a tax not based upon income, such as a minimum tax or a net worth tax.

States are continually enacting changes related to nexus and various types of taxes. As your business becomes active in other states, it’s more important than ever to discuss potential income tax exposure with your CPA. Here are some steps you can take to protect your business:

Cray Kaiser is available to help you navigate through these ever-changing requirements, and to consider potential exposure to income tax reporting as a result. If you are unsure of the requirements of states you sell into, please contact us to discuss.

One of the interesting items coming out of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) was the inclusion of specified tax breaks for taxpayers investing in low-income communities. Known as Opportunity Zones, the idea is to encourage long-term investments in low-income communities nationwide through property (real estate or equipment) or business operations.

Where Are the Opportunity Zones?

Over the last few months, the Department of the Treasury has worked with governors to designate qualified Opportunity Zones in each state. Investing in these specific areas will have tax advantages. For example, in Illinois, there are 1,305 tracts, 327 of which (25%) have been designated for Opportunity Zones. A list of the Opportunity Zones can be found here.

What Are the Tax Benefits of Opportunity Zones?

The crux of the program is to allow investors an option to reinvest their realized capital gains into opportunity funds and provide a deferral of at least a portion of the tax on the realized gain. A qualified reinvestment is primarily invested in qualified Opportunity Zones that retain their designation for at least 10 years. In order to qualify for deferral, the reinvestment into an Opportunity Zone must occur within 180 days from the date of the original sale.

For example, a capital gain that was reinvested in an Opportunity Zone and held greater than 5 years in the Opportunity Zone, 10% of the original gain will be excluded from taxes. If held in an Opportunity Zone greater than 7 years, another 5% (for total of 15%) will be excluded. In addition, if the reinvestment in an Opportunity Zone is held greater than 10 years, then not only is the original taxable capital gain reduced by 15%, but any gains from the Opportunity Zone will be excluded from capital gain tax.

For investors, this could be a great time to review any large capital gain tax exposure in order to assess whether the Opportunity Zone deferral is a good investment option given the potential to defer gains. In addition to the deferral of the original gain, the appreciation from the Opportunity Zone investment would not be subject to capital gains when disposed after 10 years. Because there are pending regulations and other requirements that need to be met in order to for Opportunity Zone designation, please contact us for more information.

The new Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction is an income tax game changer for owners of flow through entities. But there are many rules and nuances to getting the most out of the deduction. Whether your business is a Specified Service Trade or Business (SSTB), pays employee wages, has qualified property, or generates taxable income over certain thresholds can create many opportunities or obstacles for maximizing the deduction. Here is how non-SSTB owners with small employee workforces can determine the minimum amount of wages to be paid in order to maximize the QBI deduction.

The 2/7 Rule

Remember, once your taxable income exceeds $364,200 (married couples filing jointly) or $182,100 (single filers) a wage limitation is phased in. Once the threshold is breached the calculation for QBI deduction is limited to the lesser of 20% of income or 50% of wages. Therefore, the amount of wages you pay yourself or your employees can become a major factor in the QBI deduction generated. The 2/7 rule can help you determine how to adjust your wages in order to maximize your QBI deduction.

Note that there is an additional computation considering company assets, but that calculation is beyond the scope of this article and will not be considered in the following examples.

Example 1

ABC, Inc. is an S-Corp with a net taxable income of $1,000,000 before wages paid for the 2023 tax year. ABC is not an SSTB and has one owner and one employee, John Smith. John takes a modest salary from his company of only $50,000. The QBI Deduction before taking into consideration the wage limitation would be $190,000 (net income of $950,000 x 20%). However, because the company generates income that will put John over the taxable income thresholds, his QBI deduction is now limited to $25,000 (50% of $50,000).

So what should John have paid himself to maximize the QBI deduction? That’s where the 2/7 rule comes into play. Wages paid should equal 2/7 of business income. Therefore, John should pay himself a wage of $285,714 ($1,000,000*2/7). That means his net Income would be $714,286 – 20% of the net income is $142,857 which would be the same as 50% of the $285,714 of wages. The 2/7 rule generated an additional QBI deduction of $117,857. This would equate to tax savings of $43,607 ($117,857 x the 37% tax bracket).

Example 2

What if you are a small business owner that has more employees than just yourself? In that case you would take into consideration the employees’ wages along with yours.

Let’s use the same facts as example 1 except this time ABC, Inc. has employee wages of $200,000 outside of John Smith’s wages. Business income would be $800,000 before John’s wage to himself. Using the 2/7 rule, John would only need to pay himself $85,714 ($285,714-$200,000) to maximize his QBI deduction.

Additional Considerations

With the fourth quarter coming to a close, it is crucial to discuss your expected income and wages with your tax advisors to make sure you are getting the most out of your potential QBI deduction. Please contact Cray Kaiser if you’d like to discuss the QBI deduction and fourth quarter planning.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 – with its many changes impacting the 2018 tax year and beyond – brought the Qualified Business Income deduction (sometimes called the QBI deduction or 199A deduction). This new deduction can be up to 20% of the net income of a qualified business, meaning only 80% of your QBI is taxed on the federal level. But, if you are a real estate investor you are probably wondering if this deduction will apply to you. The answer is, of course, not so simple.

Defining a Qualified Trade or Business

The biggest limitation of the QBI deduction is that it only applies to a “qualified trade or business”. There is not a lot of clarity within IRS regulations in determining what exactly is a trade or business in the real estate arena and there are many unique situations concerning real estate.

The IRS cites “key factual elements” that are relevant to whether an activity is a trade or business: (a) the type of property (commercial versus residential versus personal); (b) number of properties rented; (c) day to day involvement of the owner or agent; and (d) type of lease (triple-net versus traditional). Therefore, due to the large number of actual combinations that exist in determining whether a rental activity rises to the level of a trade or business, the IRS says bright-line definitions are impractical.

Below are a few example situations that demonstrate when real estate investments would likely or likely not pass as a qualified trade or business.

We can help you determine if your rental activity facts and circumstances can give rise to a trade or business and thus allow you to be eligible for QBI. If you are not eligible, we can develop some operational strategies which can allow you to qualify for the deduction. Please contact us today at 630-953-4900.

A lot of change has come with the 2017 Tax Reform. As we adjust to the new provisions, we’re constantly learning about ways that we can shift tax planning strategies in the future to benefit and lessen tax burdens. One way to potentially minimize your taxes is with a strategy called “bunching”.

What is “Bunching”?

The near doubling of the standard deduction amount to $12,000 for single filers and $24,000 for joint filers produced the bunching strategy. With tax bunching, you move two or three years of deductible expenses into the one year you intend to itemize. For the other years, in lieu of itemizing deductions, you can claim the new higher standard deduction.

Assess Your Bunching Option

Using the bunching strategy requires some planning. First, you need to know how close you are to the standard deduction limit by reviewing your 2017 tax return. Because of the many new limits on qualified itemized deductions, you will need to estimate how close you are to the new standard deduction thresholds. Remember to limit your state and local tax deduction to $10,000 and eliminate any miscellaneous itemized deductions.

The closer your total itemized deduction total gets to the standard deduction amount for your filing status, the more the bunching strategy makes sense.

For example, John and Mary’s new itemized deduction total is about $22,000, which includes $10,000 of state taxes paid and $12,000 of charitable deductions every year. Since their itemized deductions are less than the new $24,000 standard deduction, they are losing the benefit of their itemized deductions.

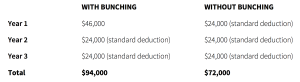

Instead, John and Mary can choose to “bunch” three years of charitable contributions into one year. Using this strategy, the couple have itemized deductions of $46,000 in year one ($10,000 of state taxes and $36,000 of charitable contributions). In years two and three, John and Mary would claim the standard deduction. Here are the deduction results:

By bunching, John and Mary are able to shift their itemized deductions to maximize the tax benefit.

If you determine that bunching is the best strategy for you, here are a few ways you can bunch your itemized deductions:

1. Review your medical and dental expenses. This is a potential bunching expense group if you project these expenses will surpass 7.5% of your income. Schedule non-emergency expenses, such as medical exams and dental cleanings, in the year you plan to clear the deduction threshold. Plan other procedures such as crowns and braces in one year instead of over many years. You can even move up health insurance premium payments.

2. Consider charitable donations as bunching options. This is the largest potential bunching area. Make all your gifts in the year you plan to surpass the standard deduction threshold. But keep an eye on the 60% of adjusted gross income (AGI) annual limit.

Alternatively, consider postponing contributions to January of the following year if you aren’t going to itemize.

3. Use mortgage interest as another bunching tool. The deduction for interest paid on new acquisition debt of up to $750,000 (or $1,000,000 if the loan was made prior to Dec. 15, 2017) is still available. Consider pre-paying the next month’s mortgage payment at the end of the year to increase the deductible interest in the year you wish to itemize.

We recommend speaking with your accountant to determine if the bunching option is best for you. Please don’t hesitate to contact Cray Kaiser with any questions.

With tuition costs rising each year, setting aside funds for college savings can be daunting. However, there are several tax options that may lessen the financial burden of college. We encourage you to review these plans with your family and your accountant to determine if one of them works for you.

Consider putting after-tax money into a Section 529 college savings account. Contributions aren’t deductible, but earnings will grow tax-free in these plans when used to pay qualifying educational expenses.

This option is best for parents and grandparents who want to save for their kids’ school tuition and other related expenses while still receiving a tax break.

The Coverdell Education Savings Account is a flexible account in which you can choose from a wide variety of investments to meet your individual needs.

This option is best for students who have education expense costs and want additional investment options for education savings.

If you’re looking for a savings option that goes beyond education, a custodial account may work well for you. With Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA) and Uniform Gift to Minors (UGMA) custodial accounts, you can generally invest in a wider variety of options versus a Section 529 plan.

This option is best for parents who give financial gifts to their kids and don’t mind handing over control of the accounts when they are 18 or older.

If you’d like to discuss these college saving options, please contact Cray Kaiser at 630-953-4900.

Many of us dream of owning a second home, but a second property can be much more than your vacation destination. In addition to a getaway for your own use, renting out your second home is a great way to offset its expense and earn extra income. But just like other types of income, the IRS expects its share of tax if your property and its use fits their definition of a “vacation rental home.” Here are some ways to determine whether your second home qualifies as a vacation rental, what needs to be reported, and what you can deduct.

Vacation homes are unique because they’re somewhere in between a rental and a personal use property. Since they’re so different, the IRS has defined several special rules for the income you earn from a vacation home, as well as what type of property qualifies as a vacation home. The property doesn’t have to fit the strict definition of a ‘home,’ since the IRS classifies a vacation home as anything that has a sleeping place, toilet, and cooking facilities. If you rent any kind of property that fits their description, from a home to a houseboat to an RV, the IRS will tax the income you earn.

The rules around how a second property is used are more complicated. According to the IRS, the amount of time that your property is used for personal use will determine whether you need to report the income and what expenses you can deduct. Here are the general guidelines:

Renting your second property can be lucrative, but don’t forget that you’ll still likely need to report the income you earn from renting your property on your taxes. We can guide you through the rules and ensure that you’re getting the best tax breaks and deductions. If you have questions about renting your second home, please don’t hesitate to contact Cray Kaiser at 630-953-4900.

On June 21, 2018 the U.S. Supreme Court held that states can assert nexus for sales and use tax purposes without requiring a seller’s physical presence in the state. While you may have heard about the Wayfair case in the news, have you thought about what this may mean for your business?

Prior to the Wayfair case, mail, phone, or internet retailers of tangible goods used the Quill case for protection from the burden of collecting sales tax. According to Quill, the protection from sales tax burdens was possible because these retailers did not have a physical presence in the form of an office, storefront, warehouse, or merely having an employee solicit the sale of goods in that state. Therefore, without stepping foot in a given state, sales in that state could be made without charging sales tax. That meant it was up to the purchaser to pay use tax on the sale.

With the Wayfair case, everything changes. Here’s what happened:

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote the decision, reasoned that modern e-commerce no longer aligns with the Quill case. Essentially, the Quill case is outdated with the large amount of commerce that is conducted via the internet. The Wayfair decision essentially overturns the Quill case and physical presence is no longer a requirement for states to assert sales tax collection requirements.

The Wayfair case will now allow all states to set their own laws in connection with interstate online sales. In fact, 31 states already have some form of laws in place. Effective October 1, 2018, retailers making sales of tangible personal property to Illinois purchasers will have to collect sales tax once Illinois sales reach $100,000 in outside sales or 200 transactions.

It is thought that the $100,000 in sales or over 200 transactions as determined in South Dakota may be the standard to determine economic sales tax nexus in other states. As noted above, this is the new standard for Illinois. If you are a retailer exceeding these numbers in states in which you don’t have physical presence, you may now have a sales tax collection and filing requirement moving forward. Congress may decide to move ahead with legislation on this issue to provide a national standard for online sales and use tax collection. We will keep you informed of future changes.

Cray Kaiser is here to help. Please contact us if you have any questions or would like guidance on a specific state’s current stance on sales tax nexus.

As your business grows, you may find yourself hiring employees out of state. While the growth associated with having an employee in another state is great, keeping up with the payroll compliance in each state can feel like trudging through murky waters. States have varying requirements related to withholding income tax and paying unemployment tax. Additionally, states have increased their tax compliance efforts over the years making it even more necessary that employers be aware of their responsibilities. So, if you have an out-of-state employee, here’s what you need to consider:

Generally, you are required to withhold income tax and pay unemployment tax in the state in which the employee physically works. Makes sense, right? But it’s not always so straightforward. If your employee travels into several states, you need to be familiar with each state’s requirements. Some states require withholding from the first day an employee works in the state while other states have thresholds (minimum numbers of days or minimum amount earned) that determine when withholding is required.

If your employee works in one state but lives in a neighboring state, he or she may have to file tax returns in both states. However, if the two states have entered into a reciprocal agreement, the employee would only need to file in the resident state.

Some states have formed reciprocal agreements, which exempt employees from paying income tax on wages earned within the state if the employee lives in a bordering state. That means that wages are only taxed by the employee’s resident state. This simplifies compliance for the employee, who would otherwise be required to file income tax returns both in the resident state and the state in which the wages were earned.

When an employee has a reciprocal exemption, the employer withholds income tax in the employee’s resident state but generally pays unemployment tax to the state in which the wages were earned. For example, consider an employee working in Illinois but living in Michigan. The employer would report the wages as Michigan wages on the payroll withholding reports, but the wages would be reported as Illinois wages for Illinois unemployment tax reports.

Payroll taxes are an obvious consideration when you have employees working in other states. You will also need to consider other workforce requirements of each state, including:

Additionally, be sure your workers’ compensation policy includes all employees, even those working remotely. In the case of remote workers, be sure to inform your workers’ compensation company of the employees’ duties, work area and work hours.

Asking yourself these questions is the first step in being compliant with the states and also providing the best possible state withholding for your employees. Cray Kaiser is available to assist you when these issues come into play. Please contact us anytime at 630-953-4900.